Georgia on my mind

Last fall, having just returned with a suitcaseful of spices from an inspiring trip to Georgia, I decided to take a group to this former Soviet republic bordered by Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia. When I threw out the idea in my newsletter, I received dozens of e-mails from students, subscribers and friends who were drawn to this off-the-beaten-path food and wine adventure. By chance the seven available spots filled up with well-travelled women, to the delight of our Georgian guide Natalia who had dreamed of organizing an all-female trip.

Our trip took place in early October, just after the grape harvest which happened a little earlier than usual this year due to a sweltering summer. We arrived in the capital just in time for Tbilisoba, an annual festival that celebrates the founding of the capital of Tbilisi. After walking across the Bridge of Peace, an impressive feat of modern architecture, we wandered through Rike Park next to the river, where skillful hands wove garlands with brightly colored flowers. With these in our hair, we suddenly felt much fresher after our long journeys. An efficient cable car costing 1 lari (about 30 cents) took us back across the river, allowing us to wend our way down through Mtatsminda Park, which offers striking views of the city.

In Tblisi we stayed at Fabrika, a pocket of hipness in a city that remains traditional to the point of having little consumer culture. This boutique hotel with simple but comfortable rooms has a facade entirely decorated by street artists who renew their creations every year. This happily coincided with our visit, so we saw the progression from nearly-bare walls when we arrived to the finished works when we returned several days later. One of the city’s most prominent street artists is Natalia’s brother George Gamez, whose cluster of fans cheered him on as he worked.

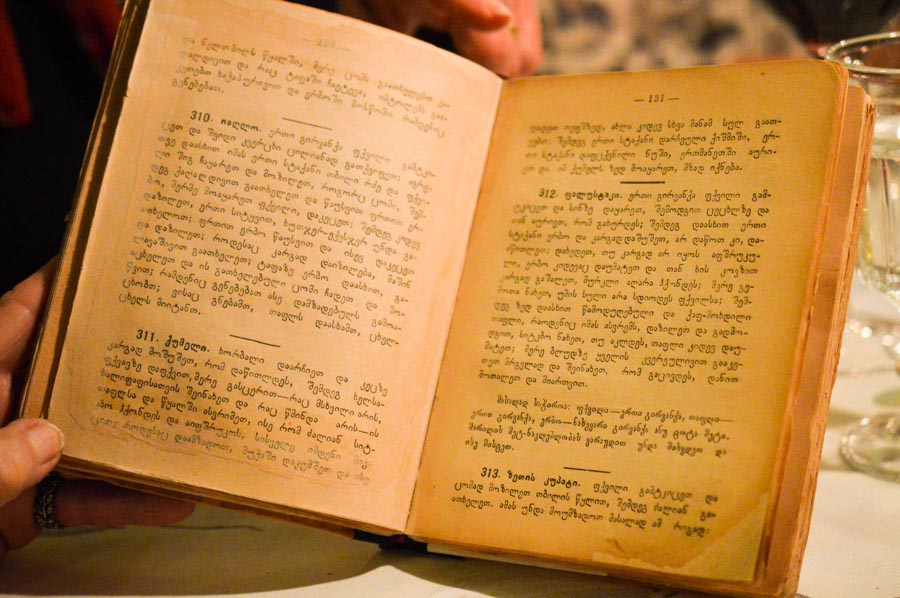

Our first dinner in Tbilisi, at Barbarestan, offered a sophisticated spin on the dishes we would encounter for the rest of the week. This former butcher shop, with meat hooks still apparent, pays tribute to the 19th-century author and feminist Barbare Jorjadze. If you ask, the waiters will bring out a precious early edition of her book, which inspires all the restaurant’s dishes. Barbarestan is run by a family with 10 children, which is lucky as the table-side service requires them to do the rounds with each dish. Every plate came heaped with herbs and wild greens, making even heavier dishes like cheese-filled flatbread seem light and refined.

The next day it was time to begin our exploration of the three main wine regions in Georgia: Kakheti to the east of the capital, and the somewhat lesser-known Kartli and Imereti to the west. The origins of wine can be traced to Georgia some 8,000 years ago, and many modern producers continue to use the traditional earthenware vessel called qvevri to produce at least some of their wines. Fermented underground with the skins, seeds and stalks for several months, these deep amber-colored wines range from funky to nectar-like, depending on the care that has gone into their production.

On the way to Sighnaghi, one of the prettiest towns in Kakheti, Natalia stopped the van at a series of roadside stalls selling fresh cheeses and breads, and led us into a simple shack where a baker was deftly slapping strips of dough onto the walls of a clay oven to make canoe-shaped breads. Known as shotis puri, this is the Georgian equivalent of Parisian baguette: no meal would be complete without it. We left with a few hot loaves which we devoured along with slices of fresh, salty cheese. A little further on we tasted another local specialty, thick and tangy buffalo-milk yoghurt served in earthenware pots. It provided the perfect foil for an array of salads including grilled eggplant and peppers and the classic Georgian combination of tomato, cucumber and red onion with fresh herbs.

After a visit to the Bodbe monastery, a working nunnery surrounded by cypress trees that is a major pilgrimage site for Georgian Orthodox Christians, we arrived in Sighnaghi for our first cooking class. I met Lali last year, and have been making the dishes she taught me ever since. This time, the whole group was amazed by the simplicity of her Georgian ratatouille, known as ajapsandali, which involves simply layering the vegetables in the pan and letting them their flavors meld, adding the tomatoes towards the end and finishing with handfuls of fresh herbs. Everyone also tried their hand at making khinkali, purse-shaped Georgian dumplings that may be filled with meat or vegetables.

As we enjoyed the fruits of our labor that night, two men at the end of our table broke into song, which is not an unusual occurrence in Georgia. Only when one of them launched into an energetic dance with almost flamenco-style hand movements did we realize we were in the presence of a master who tours the world as a musician and dance teacher. Soon we were on our feet too, thankfully freed from our inhibitions by pitchers of local wine.

The next day, after strolling through the hilltop village of Sighnaghi where we picked up hand-knitted slippers and mittens, it was time to visit our first vineyard. One of the country’s best-known wineries, the German-run Schuchmann has the look and feel of a French château and wines to match, thanks to the Georgian winemaker George Dakishvili. We learned about the qvevri method of winemaking with its traditional wooden tools before sitting down to a feast on the terrace of the elegant dining room. A highlight of this meal was the trout in plum sauce, a tangy condiment that is a staple at the Georgian table. During this meal we were able to compare the Georgian amber wine with a straw-colored white and berry-like red, each luminous in its own way.

After lunch Natalia took us to the market, or bazari, in the low-key regional capital of Telavi. I could spend hours in any Georgian bazari, sniffing spices and marveling at the many kinds of pickles, and we left this one with loaded shopping bags thanks to Natalia’s expert advice. A common sight at Georgian markets and street stalls is churchkhela, traditionally made with walnuts and thickened grape juice but now produced with other nuts and fruits as well. Looking like brightly colored sausages dangling from strings, these are one of the few traditional Georgian confectionaries, although chocolate is also popular these days.

We ended the day at Shaloshvili’s Wine Cellar in Kvareli, a peaceful spot with the Caucasus mountains providing a majestic backdrop. After tasting their impressive range of wines made with local grape varieties such as saperavi, mtsvane and rkatsiteli, we sat down to a feast of fresh salads and stewed meats. By now we were growing used to Georgian hospitality, which always involves improbable amounts of food and free-flowing wine.

The next morning it was already time to leave the Kakheti region for the historic town of Mtskheta, just north of Tbilisi. One of the oldest towns in the country and the birthplace of Georgian Orthodox Christianity, this “holy city” is a UNESCO world heritage site. Strolling through its narrow streets we discovered its artisans’ market, which although touristy for Georgia had plenty to offer in the way of quality souvenirs. Knowing my passion for ceramics Natalia took us to a local shop selling handmade pottery, where I bought two painted bowls that I now treasure.

The nearby café Floria, surrounded by waist-high wildflowers, turned out to be the perfect lunch destination. Craving something simple, we ordered grilled chicken and potato wedges with chili, as well as the Georgian salad we had come to expect at every meal.

From there we continued west towards Gori, a town best known as the birthplace of Stalin. The Stalin museum here represents a small facet of the country’s complex relationship with Russia, which still occupies land not far from this town. We were here for another purpose: to discover the wines of Kartli, a small region known for its exceptional terroir and microclimate.

We drove to Tsedisi, along a dirt road with meandering cows, to find Wine Artisans. This deceptively rustic-looking vineyard has become a center for organic wine production in Georgia thanks to charismatic owner Andro Barnovi, who offers classes and laboratory facilities for other local winemakers.

The son of a renowned winemaker, Andro had a high-flying career in politics, at one point serving as deputy minister of defense, before devoting himself to the family business. He now divides his time between Tbilisi and the vineyard, and seemed to be in his element presiding over the grill after giving us a personal tour of his pristine winery. Spinach phkali (a kind of paste made with walnuts), khachapuri with greens, lime-grilled salmon and fire-roasted carrots were among the dishes I won’t forget. Each of the wines we tasted would have been at home on the table of any Michelin-starred restaurant in France, but at that moment we much preferred Andro’s patio.

The next day, it was time for us to visit one of the most unique sites in Georgia, the Uplistsikhe cave town. Dating from around 1000 BC, this rock-hewn town that blends seamlessly into the landscape was inhabited until the 13th century. A long flight of stairs led us to the central and upper area, at the top of which is a Christian stone basilica dating from the 10th century. To my surprise, I found a small shop there selling monastery products, including medicinal herbal teas made with local plants and Georgian spices. We lost ourselves in the maze of stairways and passages, coming across rooms once dedicated to pagan sacrifices and even an old pharmacy.

Heading west into the Imereti region for the last portion of our trip, the land became more wild and forested, almost reminding me of Canada at times. The always-bubbly Natalia could barely contain her excitement as we entered her native region. “Imereti has the best food”, she said. “You’ll see!”

Our first stop at what looked like a simple roadside restaurant would confirm this. As we entered, we saw a hut with a clay oven where a baker was turning out perfectly aligned rows of fresh bread. Strings of chili peppers hung from the ceiling beams, and next to a pile of firewood a woman was patiently polishing the caps of caramel-colored mushrooms. “Those look like ceps!” exclaimed Josy, the French member of our group, and she turned out to be right, even if their color was more vivid here.

Sitting at a long wooden table, we tasted familiar dishes like grilled eggplant stuffed with garlicky walnut paste — part of just about any meal in Georgia — as well as the unforgettable mushrooms sautéed with onion and served in a clay dish, alongside spatchcocked grilled chicken that is a specialty of the region. We also tried beef stew with walnut sauce, served with a cheesy white polenta that our waitress stretched with a wooden spoon from the pot to above her head before cutting the smooth ribbon with scissors.

Our last vineyard visit was at Baia, whose 25-year-old winemaker Baia Abuladze is already attracting international attention, including an article in Food and Wine magazine, for the quality of her natural wines. Her equally passionate sister Gvantsa led our tour of the vineyard, where plants are allowed to grow wild around the vines in an approach that makes nature an ally rather than something to be tamed.

Inside the house, her mother Tamriko showed us how to prepare four staple dishes of Georgian cuisine: eggplant and walnut rolls, khachapuri (cheese bread), a red kidney bean stew known as lobio, and churchkhela, the walnut and dried fruit “candles”. Threading walnuts onto strings for these before dipping them in grape juice slowly thickened with flour over the heat, we suddenly understood why they are prized.

As Baia’s vineyard reminded us, Georgia has nature in abundance, and we spent the next day marveling at the natural wonders of Martvili Canyon and Prometheus Cave. Once a private bathing spot for a Georgian noble family called the Dadianis, Martvili is now set up for tourists but has not lost its magic. Though our group ranged in age from 45 to 79, we were all nimble enough to hop into the rafts and row along the deep turquoise river to admire the waterfall. We continued with a walk along the spectacular canyon, taking staircases that the Dadianis had once used.

Another must-see sight in the area, Prometheus is a cave discovered in 1984, named for the boulder to which the god was once chained. Led by a guide who pointed out the most striking features in the dramatic underground landscape, we followed a winding path through caves lit with colored LED lights, finishing the last portion on a boat where we donned helmets before passing through a narrow tunnel. One of our group braved her claustrophobia for the experience, and came out with no regrets.

Before returning to Tbilisi we spent a night in Kutaisi, Georgia’s administrative capital and a landing point for budget flights from European cities. Smaller and more sedate than Tbilisi, it has a walkable town center where I enjoyed a well-made cappuccino on a sidewalk terrace. A short walk from our hotel was the contemporary wine bar Sapere, which focuses on wines from the Imereti region with excellent food to match, such as soup made with local pumpkins and colorful phkali on cornbread. Not for the first time, we felt like we were in a friend’s living room rather than a restaurant.

On the way back to Tbilisi, we had to make one more stop at a bazari, this time in the town of Zestafoni, to add to our ever-growing spice collections. This being the Imereti region, one vendor was displaying perfect pyramids of white polenta, while another specialized in fresh cheeses speckled with holes, some mild and others as salty as feta.

For our last night in Georgia, we chose the restaurant Keto and Kote, named after the Georgian comic opera. At the end of a dimly lit alley, this converted house with eclectic furniture, white tablecloths and a leafy terrace with a sweeping view of the city feels like a Hollywood film set. By now our group was thoroughly bonded, and we took advantage of this last night to celebrate the birthday of Kate, who had made the trip from the US Virgin Islands. Good as all the food was in our multi-course meal, I think what we will all remember is the cake, an ethereal concoction of sponge layers, berries, pastry cream and slivered almonds. Georgia is not where I expected to taste one of the best cakes of my life, but this is a country where anything can happen.

Natalia and I will be offering a second Georgia Food and Wine Adventure from October 5-12, 2019. For more details, please sign up for my newsletter and follow Les Petits Farcis on Facebook.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!